Marta Kutas, distinguished professor of cognitive science at UC San Diego: “When I started in the cog neuro game/ there was no field, there was no name.” Photo by Erik Jepsen/UC San Diego Publications.

Marta Kutas, distinguished professor of cognitive science at UC San Diego: “When I started in the cog neuro game/ there was no field, there was no name.” Photo by Erik Jepsen/UC San Diego Publications.

Dr. Seuss of Science

By Inga Kiderra

If you spend any time around Marta Kutas, a neurolinguist and poet who has been chair of the Department of Cognitive Science at UC San Diego for a decade or so, you learn quickly that she loves words – and also that she doesn’t mince them. “I don’t care what they become,” she says of her students, “so long as it’s decent, thinking human beings!” Her voice is firm and just this side of agitated. She shrugs, “When I talk, I talk out of my heart.” She doesn’t suffer fools gladly. But spend a bit more time with her and you see that, beneath the bristles, the heart from which she speaks is soft and is sweet, a marshmallow pillow.

|

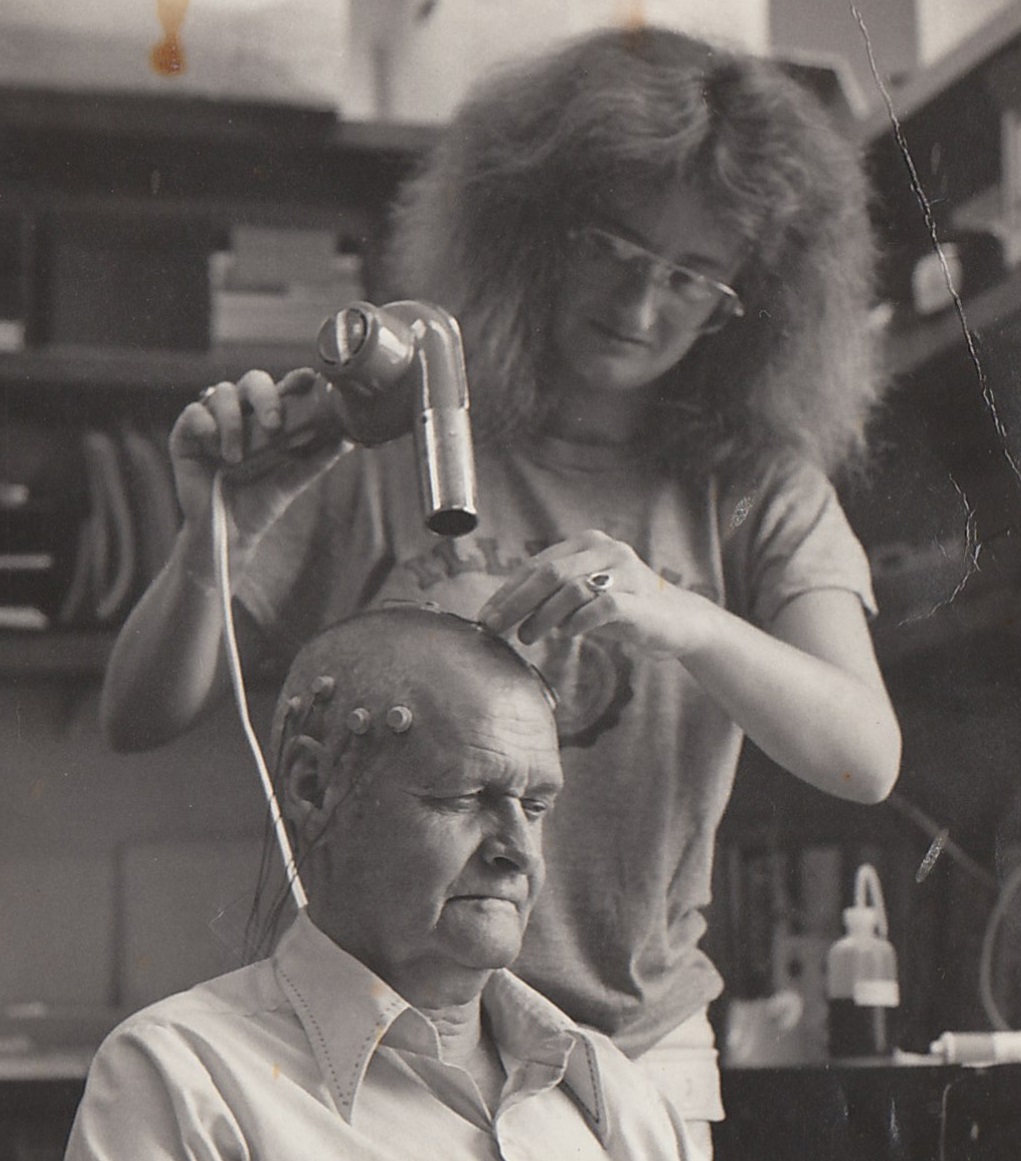

| Kutas in the 1980s, in the lab of Steven Hillyard, gluing electrodes with the help of hair dryer to the scalp of an elderly man. |

Kutas studies how the brain (or “the mind-brain”) processes language and meaning. What she means when she says she doesn’t care is that she doesn’t want to force a career in research or teaching on anyone: If a student wants to go that route, great. If they’d rather follow a dream in a different direction – and there are many places you can take a degree in cognitive science – that’s great too. Kutas, who prefers to be described more precisely as a “psychophysiologist/cognitive neuroscientist,” has been training students for more than 40 years. She has “academic children and grandchildren.” Some are professors like her, while others are succeeding in a variety of other ways. Kutas has an actual son, too, but he’s 14 and it’s unclear what career he’ll pursue. She speaks of all her progeny with pride. Getting her to talk about herself is harder – she’d rather write a poem.

Kutas was born in Hungary, in 1949. She arrived a little over eight weeks early and was placed in a homemade incubator. It was an oven, really, a big brick hearth of the kind you find in villages all over Eastern Europe. Her mother fed her from an eyedropper. She looked, she says, like a small troll: no fingernails but long black hair as long as her body.

|

| Electrodes now come on a cap. |

The family moved to Budapest in 1954, only to flee the city in 1956, during the Hungarian Revolution. Kutas recalls tanks and chaos and corpses in the street. She remembers escaping illegally one night in a truck, hidden behind a load of orange crates. They landed first in a Viennese jail then a refugee camp in Salzburg, to await papers. When the papers came, they took a prop plane across the ocean to a refugee camp in New Jersey. The experience has stayed with her more than she realized, she said. In 2017, when she and her wife decided to go to San Diego’s international airport and join a demonstration meant to show refugees that they’re still welcome in the United States, she couldn’t get out of the car. “I just sat there and cried,” she said. “Who knew?”

Kutas grew up in Cincinnati, surrounded by other immigrants and never quite fitting in. She suspects it’s in part because she always needed reasons for rules. She got in trouble at school for wearing culottes when culottes were banned. She got kicked out of a candy store for walking in with a black friend. And because she didn’t think the customer was always right, she failed at waitressing and spent her college years at Oberlin as a short order cook instead.

She drove into San Diego on New Year’s Day in 1978, shortly after finishing her Ph.D. in psychology at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. San Diego was so beautiful to her, she said, she didn’t ever want to leave. And, except to travel, she hasn’t.

Kutas started at UC San Diego as a postdoctoral scholar in neurosciences, in the School of Medicine lab of Steven Hillyard. Within a couple of years, she moved up to research scientist. Today she holds the title of Distinguished Professor in the Department of Cognitive Science. She runs the Kutas Lab and directs the Center for Research in Language. Her affiliation with the cognitive science department began in the late ’80s, right around when the department started.

|

| PCs running DOS in the Kutas Lab are “a stand against planned obsolescence.” |

Founded in 1986, the Department of Cognitive Science was the first department of its kind in the world and remains a heavy hitter in the field it helped to create. Motivated by questions on cognition – questions like “How do people, animals or computers think, learn, act and interact?” – the department brings together tools and discoveries from many different fields, including neuroscience, psychology, linguistics, anthropology, philosophy, sociology and computer science.

“I would have done my work anywhere, I think,” Kutas said. “But this department is so diverse – we have people with extremely different knowledge bases and senses of what’s important – it has stretched me and taught me humility. I’ve learned how much I don’t know.”

Kutas’ list of published papers is long. Together, they have been cited more than 30,000 times. She is perhaps best known for discovering, with Hillyard, the N400 brain wave. Recorded at the scalp with electrodes, the N400 is a measure of the brain’s response to experiencing something meaningful, at about 400 milliseconds after an event. Since its discovery in 1980, the N400 has been used in more than a 1,000 research articles. It appears to measure response not only to words – written, spoken and signed – but also to drawings, photos, videos, sounds, actions, math symbols and more.

|

| Dr. Seuss’ star-bellied Sneetches think they’re superior. Kutas identifies with the plain-bellied ones. |

Besides studying language comprehension and production in adults, Kutas studies information processing more generally, including how we learn and remember. She also investigates unconscious processes, handedness, mood and aging – normal and abnormal.

“I love science,” Kutas said, “and would love to be the ‘Dr. Seuss of Science,’ having fun with ideas and words – bringing smiles to people.”

At the 2015 meeting of the Cognitive Neuroscience Society, accepting the Distinguished Career Contributions Award, Kutas gets people smiling when she announces she’s taken “a stand against planned obsolescence” by still using a PC running DOS in her lab. “If it ain’t broke…” Also apparently not broke is her preferred method of getting at the “mind-brain” through event-related potentials, or ERPs –measurements of the brain’s electrical activity, taken at the scalp, in response to sensory, cognitive or motor events.

Her CNS talk catalogs what she’s learned in more than four decades of electrophysiological research: that “doing good science is hard but exhilarating”; that most cognitive neuroscientists are men and they’re not always cognitive; that “neither the brain nor the mind is simple, nor is there a one-to-one mapping between the two.” She’s always had one foot in psychology and one in biology, she says. And she identifies with the plain-bellied (as opposed to the snooty star-bellied) Sneetches in the Dr. Seuss story of the same name.

Her talk is also peppered with poems. Kutas started writing poetry in the early ’80s when she was bored on a trip to Joshua Tree National Park. Now it seems that everywhere she goes there’s a poem. She writes them for birthdays, memorials and books, to greet a new year, to marvel at nature, or dismay about politics. Poems show up in her emails and class handouts. Her only rule is that they must rhyme.

|

| Enrollments in the UC San Diego Department of Cognitive Science are booming. Spring 2017 saw twice as many students as ’16. |

That’s a self-imposed rule. She’s hesitant to impose rules on others. A recent edit in her Wikipedia entry (which she didn’t know about because she’s “averse to the online life people now lead”) mentions a yearlong class she’s been teaching for a while now to second-year Ph.D. students. The class aims to give students the “soft skills” they need to be successful scientists. What the soft skills are, Kutas said, is learning how to ask questions, how to give a good talk, how to find the 5-cent word instead of the 25-cent.

“We try to help each other problem-solve,” Kutas said, adding that a similar course is also required of the honors students in cognitive science. “My goal is to help people find out what they want to do. I never tell them what they should do, just make them aware of consequences to what they do do.”

In the study of the brain and behavior, everything can be data, Kutas said. It can be overwhelming. And if you are overwhelmed? “Then make it simple. Ask little questions. It’s really hard to ask questions you can actually answer.”

Above all, Kutas said, “People need to learn how to think.”

Learn more:

- CNS Q&A with Kutas

- Kutas Lab

- Center for Research in Language

- UC San Diego Department of Cognitive Science

New Year poem by Marta Kutas

2017

Can’t pretend,

upend madness,

dismiss sadness with a coy smile,

a wink or a wile.

Pretend that all is normal,

okay, though a little chaotic, disrespectful, and informal,

just another new year like all those before

where I wish you all good times and much much more,

when all I hold dear is in peril,

humanity gone unabashedly feral!

Will I cope? Will I hope?

Not really, nope!!

But in the spirit of Mohammad Ali* I do wish you

infinite wherewithal to rope your own dope.

* “Impossible is just a big word thrown around by small men who find it easier to live in the world they’ve been given than to explore the power they have to change it. Impossible is not a fact. It’s an opinion. Impossible is not a declaration. It’s a dare. Impossible is potential. Impossible is temporary. Impossible is nothing.” (Mohammad Ali, 1942-2016)