Master Networker

Education researcher Susan Yonezawa helps campus connect to local schools and build sustainable systems

By Inga Kiderra

She once rigged an election. That was in fourth grade, when she didn’t want her elementary school in Norwalk, Calif. to go by “the Redskins.” She and her buddies got caught, though, and the school went forward with the moniker. Since then, Susan Yonezawa has been on the up and up in her efforts to bring about change. She’s also been more effective.

|

| “I believe in the power of education,” Susan Yonezawa says. “It’s not the only way to level the playing field but a critical component." |

As part of the team at the UC San Diego Center for Research on Educational Equity, Assessment and Teaching Excellence, or CREATE, Yonezawa does cutting-edge research to find out how kids in underserved communities can succeed academically. She also, crucially, helps to translate that research so it doesn’t just sit on a shelf in the ivory tower.

“Education researchers have a fundamental responsibility to make education better,” Yonezawa says.

Early in her career she did a lot of what she calls “hit-and-run” work, flying in from California to study a problem in Idaho, for example, proposing a solution and then taking off. But being a member of CREATE for the past 20 years, almost since the center’s inception, has enabled Yonezawa to stick with San Diego-area schools in meaningful ways.

Past as Prologue

Yonezawa’s mom grew up on a Spreckels sugar plantation in Hawaii; the youngest of five children, she had been gifted to a childless couple who worked there. Yonezawa’s dad, one of nine kids who lost their father, emigrated from Japan as a young man not long after WWII, landing first in the Imperial Valley to pursue his American Dream.

Yonezawa was born into a working-class neighborhood in Norwalk. Save for her two older brothers, she remembers being the only Japanese-American person at schools that were predominantly Latino.

|

| Susan Yonezawa with one of her three kids. |

“From when I was pretty little, by third grade for sure, I thought it was odd that some people had advantages while others didn’t,” Yonezawa said. “‘This isn’t right…,’ I thought.”

In third grade, Yonezawa was enrolled in a pull-out GATE program. That meant being bussed once a week to a better part of town for gifted and talented education. She hated it. “It’s not that I didn’t want to do the extra work,” she says. “I hated it because I had no community there. And I couldn’t stand being treated as anointed and special.”

“I quit. I became a GATE drop-out,” she says with both amusement and pride, recalling how she had to personally explain to the GATE teacher why she didn’t want to be a part of the program anymore.

Yonezawa went to her neighborhood high school, John Glenn High. Though named after an accomplished astronaut, the school was challenged. “It was the sort of place that has 600 freshmen and 300 seniors…,” Yonezawa says, referring to the school’s low graduation rate. There were no AP classes in science or math.

She graduated class valedictorian, a year early. She and one of her closest friends both got into UCLA, though a guidance counselor did try to talk her friend, surnamed Martinez, out of going to college at all. She tells this last story with a head-shake and just the slightest trace of anger. That counselor’s bias and her own third-grade distaste for being segregated into a select group are among the formative experiences that motivate Yonezawa’s work on equity to this day.

School Reform and Student Voice

The challenges facing today’s youth, she says, are in many ways the same as they were in the ’70s and the ’80s, or before that, during segregation. “It was about access then – and it’s about access now,” she says.

Speaking from her perspective both as an education researcher and the mother of three children (one each in elementary, middle and high school), she adds: “It’s not just access to courses but access to the right courses, not just curriculum but engaging curriculum, not just pathways but personalized pathways.”

An English and psychology major as an undergraduate, Yonezawa planned to be a high school English teacher but was persuaded to pursue a doctorate at UCLA by her mentor, the late Don Nakanashi (who’s widely credited with legitimating Asian American Studies). She has no regrets about her own path.

|

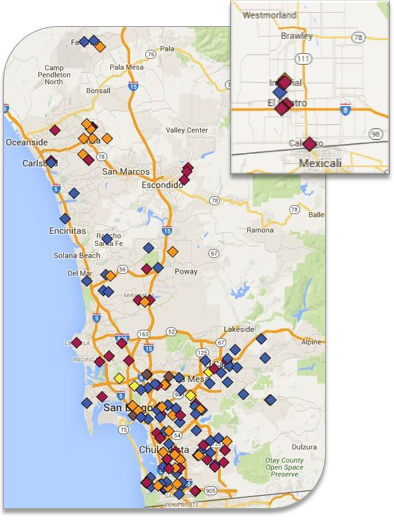

| CREATE works throughout the San Diego region. |

Now the associate director of CREATE, she gets to work every day on important issues of school reform and student voice.

“I believe in the power of education,” she says. “It’s not the only way to level the playing field but a critical component – and it’s something concrete. I like to work on concrete things.”

Her focus lately is on “making sure that young people have good job prospects – by making sure they have access to computing education, for one, and to college, more generally.”

Together with CREATE colleagues and partners in the community, Yonezawa is currently working on three major grant-funded projects. One project, the San Diego Math Network, funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, is examining and supporting networks of teachers who are interested in improving mathematics education across four local school districts: Chula Vista, San Diego, Sweetwater and Vista. In August 2017, the project hosted regional education leaders for a problem-solving symposium on the “number one stumbling block to earning a four-year degree”: Algebra II, often now taught as “Integrated III.”

Another project is funded by the Office of Naval Research – one of only two in the country, she believes, that the ONR funds on K-12 education. This project brings school teachers and researchers together to improve science education in high schools. So far, the project has touched nearly 80 teachers from 27 different high schools in four districts.

A third is an endeavor funded by the National Science Foundation to increase computer science courses and teachers in K-12 schools in three local districts. Working alongside other campus colleagues, Yonezawa has helped districts like Sweetwater, for example, grow their computer science offerings from a single course six years ago to more than 65 classrooms of high school and middle school students this year.

Connecting It All

Yonezawa also serves as the network coordinator for the CREATE STEM Success Initiative, launched in 2013 by UC San Diego Chancellor Pradeep K. Khosla. Operating as a kind of lever for local STEM education, the initiative is focused on combining the strengths of the university and the community to collectively lift education in science, technology, engineering and math throughout the San Diego region. In four years, the initiative team at CREATE has engaged with more than 450 distinct projects, helping campus and community partners to co‐design, deliver and assess K-20 STEM education efforts. Each project leverages campus resources to support students, particularly underrepresented and low‐income students, to acquire STEM skills now essential for college and career.

The common thread to Yonezawa’s work is this: She helps to connect people.

She sees her role, she says in a Diversity Award video, as “less about leading the charge and more about helping other people get the work they want to do in underserved communities done.”

It’s important not only to do the research, she says, but also to take those findings into schools, in ways that impact kids in large numbers and for the long-term. By connecting campus colleagues, staff and students with teachers, leaders and students in San Diego schools, she helps build systems that are sustainable.

“She has more local relationships than anyone I know – and is a huge wealth of research-based insights too,” says CREATE Director Mica Pollock, a professor of education studies in the UC San Diego Division of Social Sciences. “An unusual and crucial resource for CREATE and for campus, she helps us make grounded change in our region’s schools.”

The nation needs more researchers like her, Pollock adds, researchers who not only develop deep, respectful partnerships and high-quality programs with people across the community but also have deep subject-matter expertise and can play a transformative role in the field.